"10 Downing Street" - that's where the UK Prime Minister lives. But what if you were an ordinary citizen of India, say Mr. Basavaraj from Bangalore? Your address could be 56/78, 14thA Cross, 2nd Main, Garden Layout, JP Nagar 7th Phase. Landmark: Behind Sparsh Supermarket.

India has no standardised way of describing addresses as Western countries do. And a one-size-fits-all approach may not even work here because different states have their own terms like street, main/cross, colony, and more. Each address is its own little adventure. Phew!

The great Indian address!

Before the online shopping wave hit India in the early 2000s, we didn't have to pass around our addresses much. Except when a friend or relative planned to stop by or a postal package was on its way. But telling someone your address and typing it into a website/app are two very different things. This hilarious scene from the 2013 Malayalam/Tamil movie ‘Neram’ comes to mind, where Johnykutty (played by Lalu Alex) goes to file an FIR and begins a lengthy explanation of his address and the irate policeman snaps at him, “Don’t explain the route to me—just tell me your address and door number!”

When describing an address to a delivery person, we might mention landmarks just like Johnykutty does: a big green building or a store across the street. But while filling out the address fields on any e-commerce app, we are asked for specific details such as house/door number, building name, street, area, and pincode.

Not all addresses follow the same format and many people may not even know the specifics of their own address. Consider a person in a densely populated Mumbai chawl or another in a rural farmland or mountain village where homes are scattered far apart. How do they describe their locations? And how does a delivery person decode these clues to reach the right destination?

These questions took us on a fascinating journey. We dug into the intricate puzzle of Indian addresses and how people navigate ecommerce address fields to get their online orders delivered. For this story, we reached out to folks living in a variety of settings: urban slums, chawls, remote mountain villages, and rural farmlands in India. Here are some common themes that emerged.

Long live mobile number.

Imagine trying to deliver a package in a sparsely populated area like a mountainous region or a deep rural setting. Homes are scattered far and wide, and many of them lack clear identifiers like door numbers or names. Sometimes, an address is just a village and town name. For a delivery person, finding these places can feel like a treasure hunt. Hence, the delivery person often needs to call the customers ahead of time. This helps to confirm the exact location and plan the most efficient delivery route.

Priyanka, who operates a design studio in Bangalore, recently spent some time in a tiny Himachal Pradesh village. During her stay, she frequently used Amazon for her shopping needs. She shared with us how the delivery process worked in such a remote location.

“They (Delivery executives) usually call everyone who has a delivery in the morning to confirm the address. For some addresses they will have to park their vehicle in the main road and walk some distance to reach the customer's home. The Myntra guy would specifically ask to place a return order, (in case any) by the evening. If I did it before that he would be assigned instantly and he would have to come back to get the parcel while he is addressing other deliveries. By placing the return in evening he would be assigned for the next day"

Making sure to provide the correct mobile number is vital for customers to coordinate delivery. Customers often give an alternate number as a backup if the first one is unavailable. If the delivery person can't get in touch with the customer, the delivery gets postponed to the next day.

Give me the landmark.

When structured addresses are lacking, landmarks become significant in pinpointing the correct home. These landmarks can range from a well-known school or temple to a popular restaurant or bus stop.

Kavya, from a small village in Karnataka, uses a different tactic. Her delivery address typically includes "C/O", followed by her husband's or father's name, to help the delivery person identify the home quickly. If the delivery person calls when nearby, she uses a large banyan tree as a landmark. If confusion persists, they go to meet the delivery person for the pick-up.

It is not uncommon for prominent individuals in a community to become recognized as landmarks in their own right. In some cases, even the Royal Enfields parked outside their homes can serve as a distinctive identifier.

Unofficial delivery hubs

In areas where coordinating deliveries is difficult, local shops often serve as drop-off points. The delivery personnel leave the packages at these locations, and the customers then pick up their deliveries from these shops.

Navin resides in a small village near Almora in Uttarakhand. The village shares a single pincode with multiple neighbouring villages. Although e-commerce websites claim to provide service to this pincode, the delivery executives often refuse to deliver to Navin's location, citing difficulties in finding the address. Consequently, Navin frequently faces situations where his orders are returned, with the excuse of the unavailability of the customer, even though no delivery attempt was made.

Alternatively, some courier companies choose to leave their deliveries at a well-known general store located a few kilometres away from the villages. Customers are then asked to pick up their parcels from there. The general store owner has designated a steel almirah to stack up these packages, and the pickup process relies on trust. The OTP for delivery confirmation is shared over the phone.

At the mercy of the delivery person

In various regions, familiar delivery personnel serve the same areas over an extended period, developing a close knowledge of the inner streets. They establish relationships with local vendors and shopkeepers, becoming familiar faces themselves.

Shipments sent through India Post generally reach the correct addresses with ease, thanks to the postmen, often locals or individuals who have mastered navigating the streets. However, with courier companies, this may not always be the case. They might hire non-locals or change delivery personnel frequently, leading to a reliance on the attitude of the current delivery person for timely receipt of the courier.

Ms Vijaya, an NGO worker, shared her experience stating that delivery boys are usually accommodating when the addresses are not precise, going the extra mile to call and coordinate. In certain areas where delivery executives fear robbery, they may refuse to deliver or return orders without attempting delivery. These locations with robbery concerns are often known through tribal knowledge accumulated over time.

Good UX = Better address input.

Digital apps have created clever ways to make it easier for users to enter their addresses. Some websites simply ask for your postal code. Once you enter it, they automatically fill in the town, district, and state details for you.

Amazon does something similar. It suggests addresses from Google Maps, and you just pick the one that's right for you.

Bharat Agri, an app for farmers to order goods, lets users optionally upload an ID proof to confirm their address.

Swiggy's new app, 'Insanely Good', has an interesting feature. It lets users optionally upload a picture of their front door. This helps in scheduling deliveries of groceries and other items.

But there's only so much that smart design and technology can do. They can't solve everything.

Startups trying to solve this challenge

For years, different startups have tried to solve the non-standard address problem. A common method was to create a unique code for each address, kind of like a personal ID. In 2015, a startup called Easyzip joined forces with BBMP to spread these unique codes across Bangalore. Today, though the startup has disappeared from the online world, their code boards are still visible around Bangalore

We had the chance to talk to Anand Sukumaran, who founded Zeocode. This was one of the first startups to attempt to standardise addresses and was active between 2013 and 2015. We asked Anand about the main obstacles to standardising addresses, and here's what he shared:

“A big reason why I believe our solution wasn't the best is the public's reluctance to adopt geo-coded locations in a specific format. People identify with their streets. It's part of their identity. If you replace that with a code, it feels foreign and impersonal.

In my opinion, a better approach is a uniform address system designed and implemented by the government. A simpler system, for instance, using just the door number and street number. Of course, this needs to be well-planned. How should the city be structured? How should different areas be designated? What about the various pockets and streets? If the government could design such a system and make it uniform, it would be easier for people to adopt.”

D2C brands and razor-thin margins.

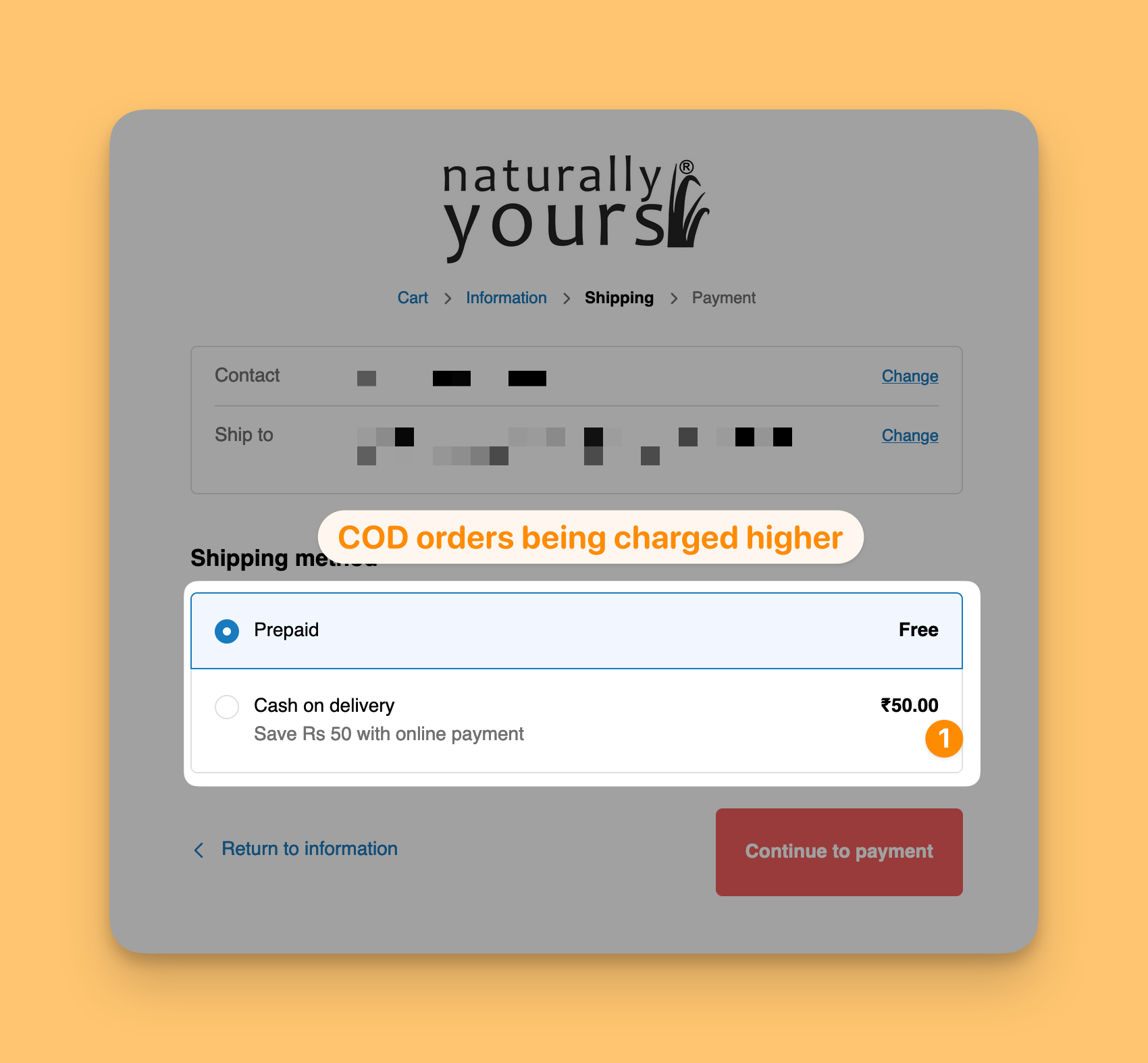

Online shopping and trust in e-commerce are still relatively new ideas for many Indians. Most people prefer to use Cash on Delivery (COD) when ordering online. I wondered if these non-standard addresses could pose a problem for e-commerce deliveries, especially for Direct-to-Consumer (D2C) businesses, which often work with very slim profit margins. We had a chat with Abhijeet Gaur, who has a lot of experience dealing with the issue of non-standard addresses in e-commerce with his experience at Razorpay and currently at Bureau.

“Out of all the returns in the COD orders, 50% are due to bad addresses, and the other 50% are due to bad intentions. Let's consider Flatheads or Neiman's; these guys operate on razor-thin margins, right? So they aim to understand why a customer placed a COD order but didn't receive it. To achieve this, they incorporate something called NDR data (Non-Delivery Report). When an COD return occurs, they call the end customer and inquire whether the delivery guy attempted a delivery or not. This serves as a reconciliation process. If the delivery guy claims they tried delivering and the customer denies receiving any call, how do they resolve the dispute? Here's where the NDR data comes in handy. They observe that the users responsible for many of these Return to Origin (RTO) cases are not answering their calls, even the NDR calls. Consequently, they start creating a blacklist of such users.

In the past, this process used to be passive, but nowadays, many early-stage D2C providers have taken a proactive approach. They no longer deliver to certain PIN codes known for frequent non-deliverability. If we analyze the data, we typically find tier three and tier two areas in India to be the ones where non-deliverability occurs. For most D2C companies, they have about 70% successful delivery rates in tier one, 50% or less in tier two, and less than 30-35% in tier three.

The delivery rate in tier two is impacted by issues like incomplete addresses or delivery providers hesitating to deliver. These areas often rely on specific local delivery vendors that have a good track record, such as Blue Dart or DTDC. These companies excel in certain states like MP, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. So, even in tier three and tier four regions, they might charge a bit more for delivery but ensure successful delivery. This valuable knowledge becomes a navigational tactic for successful D2C companies, acquired over time by analyzing a lot of data."

Conclusion

An individual’s address is more than just a place of residence. It’s an identity. In a recent youtube interview a filmmaker said this statement - ‘Tell me your street name, and I will tell you your caste’. It resonated hard with me. Even today the smaller towns of India are largely divided by the caste and religion residing in their corresponding localities. Delivery executives refusing to go inside a slum or refusing deliveries to certain pincode as they suspect fraud or asking customers to come to their office and get the parcel are all a part of the biases that we form on people based on who they are and where they come from. The next time when you fill the address fields on e-commerce websites if you are able to fill the fields with correct details appropriately then consider yourself privileged.